| |

Austria-Hungary 1867-1918 |

Austria-Hungary (W)

Austria-Hungary 1867-1918 (W)

| Capital |

Vienna (Cisleithania) and

Budapest (Transleithania) |

| Official languages |

Other spoken languages:

Bosnian, Czech, Romani (Carpathian), Romanian, Rusyn, Ruthenian, Serbian, Slovak, Slovene, Ukrainian, Yiddish |

| Religion

|

76.6% Catholic (incl. 64-66% Latin & 10-12% Eastern)

8.9% Protestant (Lutheran, Reformed, Unitarian)

8.7% Orthodox

4.4% Jewish

1.3% Muslim

(1910 census) |

| Demonym(s) |

Austro-Hungarian |

| Government |

Constitutional dual monarchy |

| Emperor-King |

|

|

• 1867–1916 |

Franz Joseph I |

• 1916–1918 |

Karl I & IV |

| Minister-President of Austria |

|

|

• 1867 (first) |

F. F. von Beust |

• 1918 (last) |

Heinrich Lammasch |

| Prime Minister of Hungary |

|

|

• 1867–1871 (first) |

Gyula Andrássy |

• 1918 (last) |

János Hadik |

| Legislature |

2 national legislatures |

|

Herrenhaus

Abgeordnetenhaus |

|

House of Magnates

House of Representatives |

| Historical era |

New Imperialism • World War I |

|

|

30 March 1867 |

|

7 October 1879 |

|

6 October 1908 |

|

28 June 1914 |

|

28 July 1914 |

|

31 October 1918 |

|

12 November 1918 |

|

16 November 1918 |

|

10 September 1919 |

|

4 June 1920 |

| Area |

| 1905 |

621,537.58 km2 (239,977.00 sq mi) |

| Population |

|

• 1914 |

52,800,000 |

| Currency |

|

|

|

|

There were three parts to the rule of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

- the common foreign, military and a joint financial policy (only for diplomatic, military and naval expenditures) under the monarch

- the "Austrian" or Cisleithanian government

- the Hungarian government

|

← common emperor-king,

common ministries

← entities

← partner states |

|

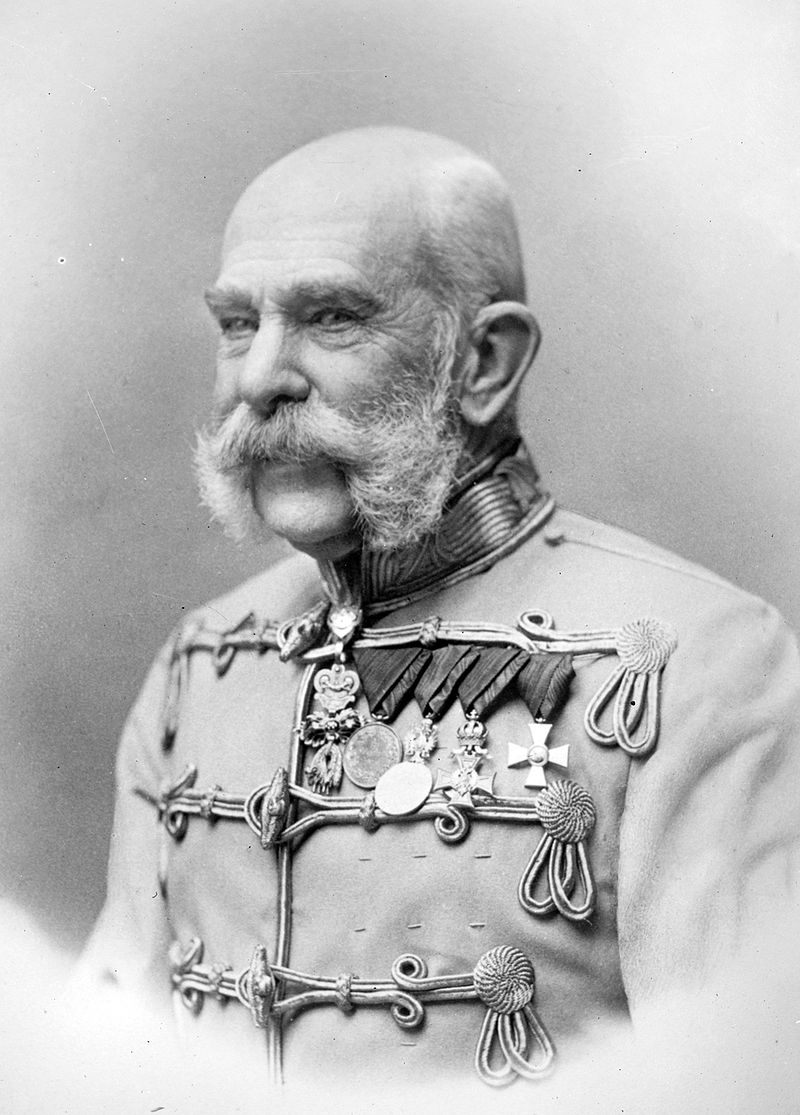

Emperor Franz Joseph I in 1905. |

|

|

| |

|

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire or the Dual Monarchy, was a constitutional monarchy in Central and Eastern Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed when the Austrian Empire adopted a new constitution; as a result Austria (Cisleithania) and Hungary (Transleithania) were placed on equal footing. It dissolved when its member states proclaimed sovereignty and independence following the First World War.

The union was established by the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 on 30 March 1867 in the aftermath of the Austro-Prussian War. It consisted of two monarchies (Austria and Hungary), and one autonomous region: the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia under the Hungarian crown, which negotiated the Croatian-Hungarian Settlement in 1868. It was ruled by the House of Habsburg, and constituted the last phase in the constitutional evolution of the Habsburg Monarchy. Following the 1867 reforms, the Austrian and Hungarian states were co-equal in power. Foreign and military affairs came under joint oversight, but all other governmental faculties were divided between respective states.

Austria-Hungary was a multinational state and one of Europe's major powers at the time. Austria-Hungary was geographically the second-largest country in Europe after the Russian Empire, at 621,538 km2 (239,977 sq mi), and the third-most populous (after Russia and the German Empire). The Empire built up the fourth-largest machine building industry of the world, after the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Austria-Hungary also became the world’s third largest manufacturer and exporter of electric home appliances, electric industrial appliances and power generation apparatus for power plants, after the United States and the German Empire.

After 1878, Bosnia and Herzegovina came under Austro-Hungarian military and civilian rule until it was fully annexed in 1908, provoking the Bosnian crisis among the other powers. The northern part of the Ottoman Sanjak of Novi Pazar was also under de facto joint occupation during that period but the Austro-Hungarian army withdrew as part of their annexation of Bosnia. The annexation of Bosnia also led to Islam being recognized as an official state religion due to Bosnia's Muslim population.

Austria-Hungary was one of the Central Powers in World War I, which began with an Austro-Hungarian war declaration on the Kingdom of Serbia on 28 July 1914. It was already effectively dissolved by the time the military authorities signed the armistice of Villa Giusti on 3 November 1918. The Kingdom of Hungary and the First Austrian Republic were treated as its successors de jure, whereas the independence of the West Slavs and South Slavs of the Empire as the First Czechoslovak Republic, the Second Polish Republic and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, respectively, and most of the territorial demands of the Kingdom of Romania were also recognized by the victorious powers in 1920. |

| |

Ethno-linguistic map of Austria-Hungary, 1910. |

|

Structure and name (W)

The realm's official name was in German: Österreichisch-Ungarische Monarchie and in Hungarian: Osztrák–Magyar Monarchia (English: Austro-Hungarian Monarchy), though in international relations Austria-Hungary was used (German: Österreich-Ungarn, Hungarian: Ausztria-Magyarország). The Austrians also used the names k. u. k. Monarchie (English: "k. u. k. monarchy) (in detail German: Kaiserliche und königliche Monarchie Österreich-Ungarn, Hungarian: Császári és Királyi Osztrák–Magyar Monarchia) and Danubian Monarchy (German: Donaumonarchie, Hungarian: Dunai Monarchia) or Dual Monarchy (German: Doppel-Monarchie, Hungarian: Dual-Monarchia) and The Double Eagle (German: Der Doppel-Adler, Hungarian: Kétsas), but none of these became widespread either in Hungary, or elsewhere.

The realm's full name used in the internal administration was The Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council and the Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of St. Stephen.

German: Die im Reichsrat vertretenen Königreiche und Länder und die Länder der Heiligen Ungarischen Stephanskrone

Hungarian: A Birodalmi Tanácsban képviselt királyságok és országok és a Magyar Szent Korona országai

The Habsburg monarch ruled as Emperor of Austria over the western and northern half of the country that was the Austrian Empire ("Lands Represented in the Imperial Council", or Cisleithania) and as King of Hungary over the Kingdom of Hungary ("Lands of the Crown of Saint Stephen”, or Transleithania). Each enjoyed considerable sovereignty with only a few joint affairs (principally foreign relations and defence).

Certain regions, such as Polish Galicia within Cisleithania and Croatia within Transleithania, enjoyed autonomous status, each with its own unique governmental structures (see: Polish Autonomy in Galicia and Croatian–Hungarian Settlement).

The division between Austria and Hungary was so marked that there was no common citizenship: one was either an Austrian citizen or a Hungarian citizen, never both. This also meant that there were always separate Austrian and Hungarian passports, never a common one. However, neither Austrian nor Hungarian passports were used in the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia. Instead, the Kingdom issued its own passports which were written in Croatian and French and displayed the coat of arms of the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia-Dalmatia on them. It is not known what kind of passports were used in Bosnia-Herzegovina, which was under the control of both Austria and Hungary.

Hungarian Parliament building. |

|

The Kingdom of Hungary had always maintained a separate parliament, the Diet of Hungary, even after the Austrian Empire was created in 1804. The administration and government of the Kingdom of Hungary (until 1848-49 Hungarian revolution) remained largely untouched by the government structure of the overarching Austrian Empire. Hungary's central government structures remained well separated from the Austrian imperial government. The country was governed by the Council of Lieutenancy of Hungary (the Gubernium) – located in Pressburg and later in Pest – and by the Hungarian Royal Court Chancellery in Vienna. The Hungarian government and Hungarian parliament were suspended after the Hungarian revolution of 1848, and were reinstated after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise in 1867.

Despite Austria and Hungary sharing a common currency, they were fiscally sovereign and independent entities. Since the beginnings of the personal union (from 1527), the government of the Kingdom of Hungary could preserve its separate and independent budget. After the revolution of 1848-1849, the Hungarian budget was amalgamated with the Austrian, and it was only after the Compromise of 1867 that Hungary obtained a separate budget. From 1527 (the creation of the monarchic personal union) to 1851, the Kingdom of Hungary maintained its own customs controls, which separated her from the other parts of the Habsburg-ruled territories. After 1867, the Austrian and Hungarian customs union agreement had to be renegotiated and stipulated every ten years. The agreements were renewed and signed by Vienna and Budapest at the end of every decade because both countries hoped to derive mutual economic benefit from the customs union. The Austrian Empire and Kingdom of Hungary contracted their foreign commercial treaties independently of each other.

Austria-Hungary was a great power but it contained a large number of ethnic groups that sought their own nation. The Dual Monarchy was effectively ruled by a coalition of the two most powerful and numerous ethnic groups, the Germans and the Hungarians. Stresses regarding nationalism were building up, and the severe shock of a poorly handled war caused the system to collapse.

Vienna served as the Monarchy's primary capital. The Cisleithanian (Austrian) part contained about 57 percent of the total population and the larger share of its economic resources, compared to the Hungarian part.

Following a decision of Franz Joseph I in 1868, the realm bore the official name Austro-Hungarian Monarchy/Realm (German: Österreichisch-Ungarische Monarchie/Reich; Hungarian: Osztrák–Magyar Monarchia/Birodalom) in its international relations. It was often contracted to the Dual Monarchy in English, or simply referred to as Austria. |

Creation (W)

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 (called the Ausgleich in German and the Kiegyezés in Hungarian), which inaugurated the empire's dual structure in place of the former Austrian Empire (1804-1867), originated at a time when Austria had declined in strength and in power — both in the Italian Peninsula (as a result of the Second Italian War of Independence of 1859) and among the states of the German Confederation (it had been surpassed by Prussia as the dominant German-speaking power following the Austro-Prussian War of 1866). The Compromise re-established the full sovereignty of the Kingdom of Hungary, which was lost after the Hungarian Revolution of 1848.

Other factors in the constitutional changes were continued Hungarian dissatisfaction with rule from Vienna and increasing national consciousness on the part of other nationalities (or ethnicities) of the Austrian Empire. Hungarian dissatisfaction arose partly from Austria's suppression with Russian support of the Hungarian liberal revolution of 1848/49. However, dissatisfaction with Austrian rule had grown for many years within Hungary and had many other causes.

By the late 1850s, a large number of Hungarians who had supported the 1848-49 revolution were willing to accept the Habsburg monarchy. They argued that while Hungary had the right to full internal independence, under the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713, foreign affairs and defense were "common" to both Austria and Hungary.

After the Austrian defeat at Königgrätz, the government realized it needed to reconcile with Hungary to regain the status of a great power. The new foreign minister, Count Friedrich Ferdinand von Beust, wanted to conclude the stalemated negotiations with the Hungarians. To secure the monarchy, Emperor Franz Joseph began negotiations for a compromise with the Hungarian nobility, led by Ferenc Deák, to ensure their support. In particular, Hungarian leaders demanded and received the Emperor's coronation as King of Hungary and the re-establishment of a separate parliament at Pest with powers to enact laws for the lands of the Holy Crown of Hungary.

From 1867 onwards, the abbreviations heading the names of official institutions in Austria-Hungary reflected their responsibility: k. u. k. (kaiserlich und königlich or Imperial and Royal) was the label for institutions common to both parts of the Monarchy, e.g. the k.u.k. Kriegsmarine (War Fleet) and, during the war, the k.u.k. Armee (Army). There were three k.u.k. or joint ministries:

- The Imperial and Royal Ministry of the Exterior and the Imperial House

- The Imperial and Royal War Ministry

- The Imperial and Royal Ministry of Finance

The last was responsible only for financing the Imperial and Royal household, the diplomatic service, the common army and the common war fleet. All other state functions were to be handled separately by each of the two states.

From 1867 onwards, common expenditures were allocated 70% to Austria and 30% to Hungary. This split had to be negotiated every decade. By 1907, the Hungarian share had risen to 36.4%. The negotiations in 1917 ended with the dissolution of the Dual Monarchy.

The common army changed its label from k.k. to k.u.k. only in 1889 at the request of the Hungarian government.

|

Dissolution (W)

The Austro-Hungarian Monarchy collapsed with dramatic speed in the autumn of 1918. In the capital cities of Vienna and Budapest, the leftist and liberal movements and politicians (the opposition parties) strengthened and supported the separatism of ethnic minorities. These leftist or left-liberal pro-Entente maverick parties opposed the monarchy as a form of government and considered themselves internationalist rather than patriotic. Eventually, the German defeat and the minor revolutions in Vienna and Budapest gave political power to the left/liberal political parties. As it became apparent that the Allied powers would win World War I, nationalist movements, which had previously been calling for a greater degree of autonomy for various areas, started pressing for full independence. The Emperor had lost much of his power to rule, as his realm disintegrated.

Alexander Watson argues that, "The Habsburg regime's doom was sealed when Wilson's response to the note, sent two and a half weeks earlier, arrived on 20 October." Wilson rejected the continuation of the dual monarchy as a negotiable possibility. As one of his Fourteen Points, President Woodrow Wilson demanded that the nationalities of Austria-Hungary have the “freest opportunity to autonomous development.” In response, Emperor Karl I agreed to reconvene the Imperial Parliament in 1917 and allow the creation of a confederation with each national group exercising self-governance. However, the leaders of these national groups rejected the idea; they deeply distrusted Vienna and were now determined to get independence.

On 14 October 1918, Foreign Minister Baron István Burián von Rajecz asked for an armistice based on the Fourteen Points. In an apparent attempt to demonstrate good faith, Emperor Karl issued a proclamation ("Imperial Manifesto of 16 October 1918") two days later which would have significantly altered the structure of the Austrian half of the monarchy. The Polish majority regions of Galicia and Lodomeria were to be granted the option of seceding from the empire, and it was understood that they would join their ethnic brethren in Russia and Germany in resurrecting a Polish state. The rest of Cisleithania was transformed into a federal union composed of four parts — German, Czech, South Slav and Ukrainian. Each of these was to be governed by a national council that would negotiate the future of the empire with Vienna. Trieste was to receive a special status. No such proclamation could be issued in Hungary, where Hungarian aristocrats still believed they could subdue other nationalities and maintain the "Holy Kingdom of St. Stephen".

It was a dead letter. Four days later, on 18 October, United States Secretary of State Robert Lansing replied that the Allies were now committed to the causes of the Czechs, Slovaks and South Slavs. Therefore, Lansing said, autonomy for the nationalities – the tenth of the Fourteen Points – was no longer enough and Washington could not deal on the basis of the Fourteen Points anymore. In fact, a Czechoslovak provisional government had joined the Allies on 14 October. The South Slavs in both halves of the monarchy had already declared in favor of uniting with Serbia in a large South Slav state by way of the 1917 Corfu Declaration signed by members of the Yugoslav Committee. Indeed, the Croatians had begun disregarding orders from Budapest earlier in October.

The Lansing note was, in effect, the death certificate of Austria-Hungary. The national councils had already begun acting more or less as provisional governments of independent countries. With defeat in the war imminent after the Italian offensive in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto on 24 October, Czech politicians peacefully took over command in Prague on 28 October (later declared the birthday of Czechoslovakia) and followed up in other major cities in the next few days. On 30 October, the Slovaks followed in Martin. On 29 October, the Slavs in both portions of what remained of Austria-Hungary proclaimed the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. They also declared that their ultimate intention was to unite with Serbia and Montenegro in a large South Slav state. On the same day, the Czechs and Slovaks formally proclaimed the establishment of Czechoslovakia as an independent state.

In Hungary, the most prominent opponent of continued union with Austria, Count Mihály Károlyi, seized power in the Aster Revolution on 31 October. Charles was all but forced to appoint Károlyi as his Hungarian prime minister. One of Károlyi's first acts was to cancel the compromise agreement, officially dissolving the Austro-Hungarian state.

By the end of October, there was nothing left of the Habsburg realm but its majority-German Danubian and Alpine provinces, and Karl's authority was being challenged even there by the German-Austrian state council. Karl's last Austrian prime minister, Heinrich Lammasch, concluded that Karl was in an impossible situation, and persuaded Karl that the best course was to relinquish, at least temporarily, his right to exercise sovereign authority.

|

|

|

|

Austria-Hungary (B)

Austria-Hungary 1867-1918 (B)

Map showing the extent of Austria-Hungary, 1914. |

Alternative Titles: Österreich-Ungarn, Österreichisch-Ungarische Monarchie, Österreichisch-Ungarisches Reich, Austro-Hungarian Empire, Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, Doppelmonarchie, Dual Monarchy

Austria-Hungary, also called Austro-Hungarian Empire or Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, byname Dual Monarchy, German Österreich-Ungarn, Österreichisch-Ungarisches Reich, Österreichisch-Ungarische Monarchie, or Doppelmonarchie, the Habsburg empire from the constitutional Compromise (Ausgleich) of 1867 between Austria and Hungary until the empire’s collapse in 1918.

|

The empire of Austria, as an official designation of the territories ruled by the Habsburg monarchy, dates to 1804, when Francis II, the last of the Holy Roman emperors, proclaimed himself emperor of Austria as Francis I. Two years later the Holy Roman Empire came to an end. After the fall of Napoleon (1814-15), Austria became once more the leader of the German states, but the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 resulted in the expulsion of Austria from the German Confederation and caused Emperor Franz Joseph to reorient his policy toward the east and to consolidate his heterogeneous empire. Even before the war, the necessity of coming to terms with the rebellious Hungarians had been recognized. The outcome of negotiations was the Ausgleich concluded on February 8, 1867.

Franz-Joseph-1908. |

|

|

| |

|

The agreement was a compromise between the emperor and Hungary, not between Hungary and the rest of the empire. Indeed, the peoples of the empire were not consulted, despite Franz Joseph’s earlier promise not to make further constitutional changes without the advice of the imperial parliament, the Reichsrat. Hungary received full internal autonomy, together with a responsible ministry, and, in return, agreed that the empire should still be a single great state for purposes of war and foreign affairs. Franz Joseph thus surrendered his domestic prerogatives in Hungary, including his protection of the non-Magyar peoples, in exchange for the maintenance of dynastic prestige abroad. The “common monarchy” consisted of the emperor and his court, the minister for foreign affairs, and the minister of war. There was no common prime minister (other than Franz Joseph himself) and no common cabinet. The common affairs were to be considered at the delegations, composed of representatives from the two parliaments. There was to be a customs union and a sharing of accounts, which was to be revised every 10 years. This decennial revision gave the Hungarians recurring opportunity to levy blackmail on the rest of the empire.

The Ausgleich came into force when passed as a constitutional law by the Hungarian parliament in March 1867. The Reichsrat was only permitted to confirm the Ausgleich without amending it. In return for this, the German liberals, who composed its majority, received certain concessions: the rights of the individual were secured, and a genuinely impartial judiciary was created; freedom of belief and of education were guaranteed. The ministers, however, were still responsible to the emperor, not to a majority of the Reichsrat.

The official name of the state shaped by the Ausgleich was Austria-Hungary. The kingdom of Hungary had a name, a king, and a history of its own. The rest of the empire was a casual agglomeration without even a clear description. Technically, it was known as “the kingdoms and lands represented in the Reichsrat” or, more shortly, as “the other Imperial half.” The mistaken practice soon grew of describing this nameless unit as “Austria” or “Austria proper” or “the lesser Austria”—names all strictly incorrect until the title “empire of Austria” was restricted to “the other Imperial half” in 1915. These confusions had a simple cause: the empire of Austria with its various fragments was the dynastic possession of the house of Habsburg, not a state with any common consciousness or purpose. |

|

|

|

|

|

|