An artist’s impression of Burgundian knights in gothic armour. |

|

|

| |

|

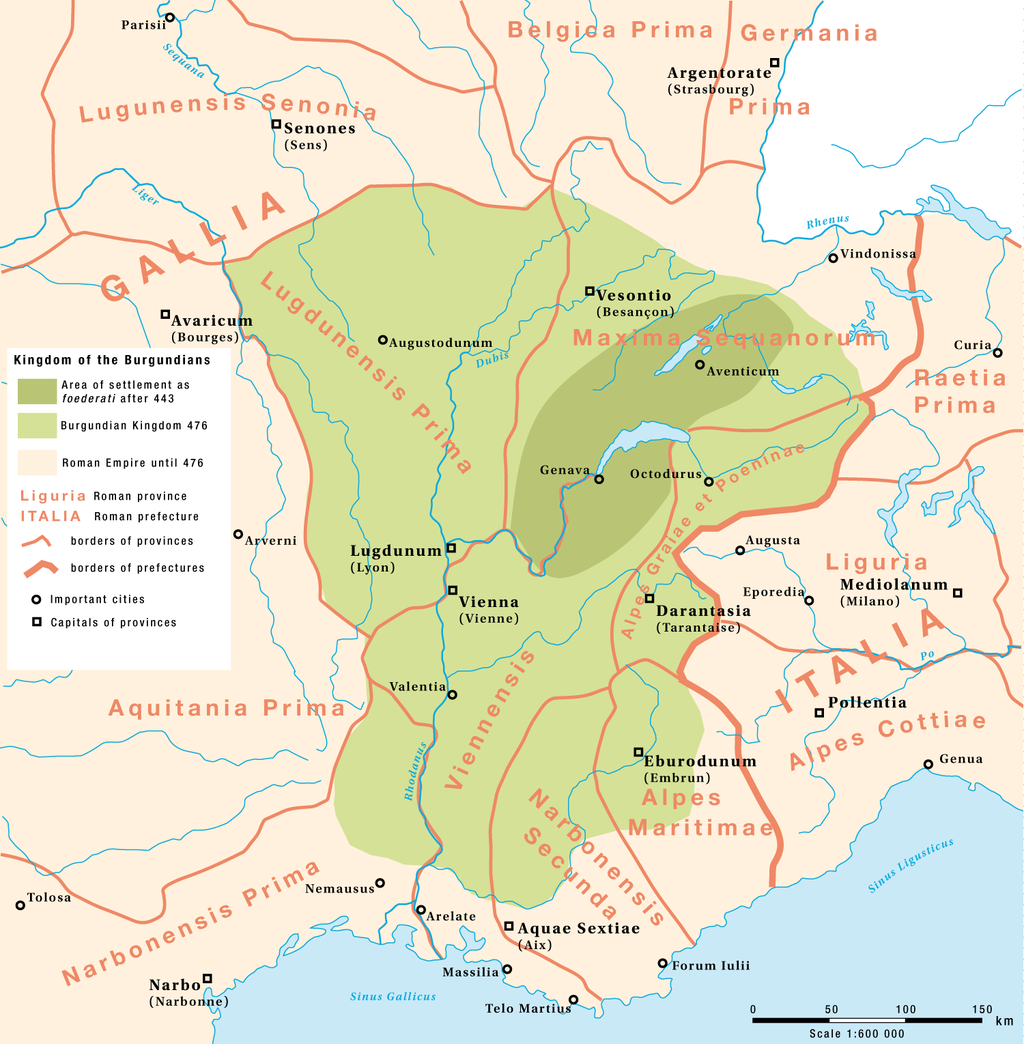

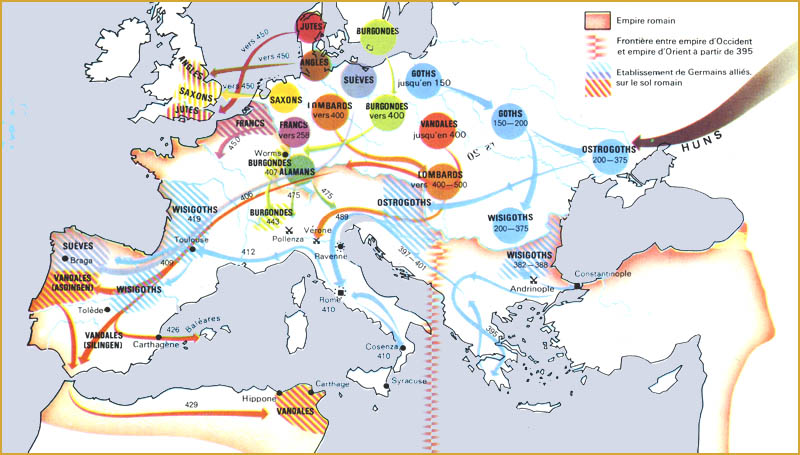

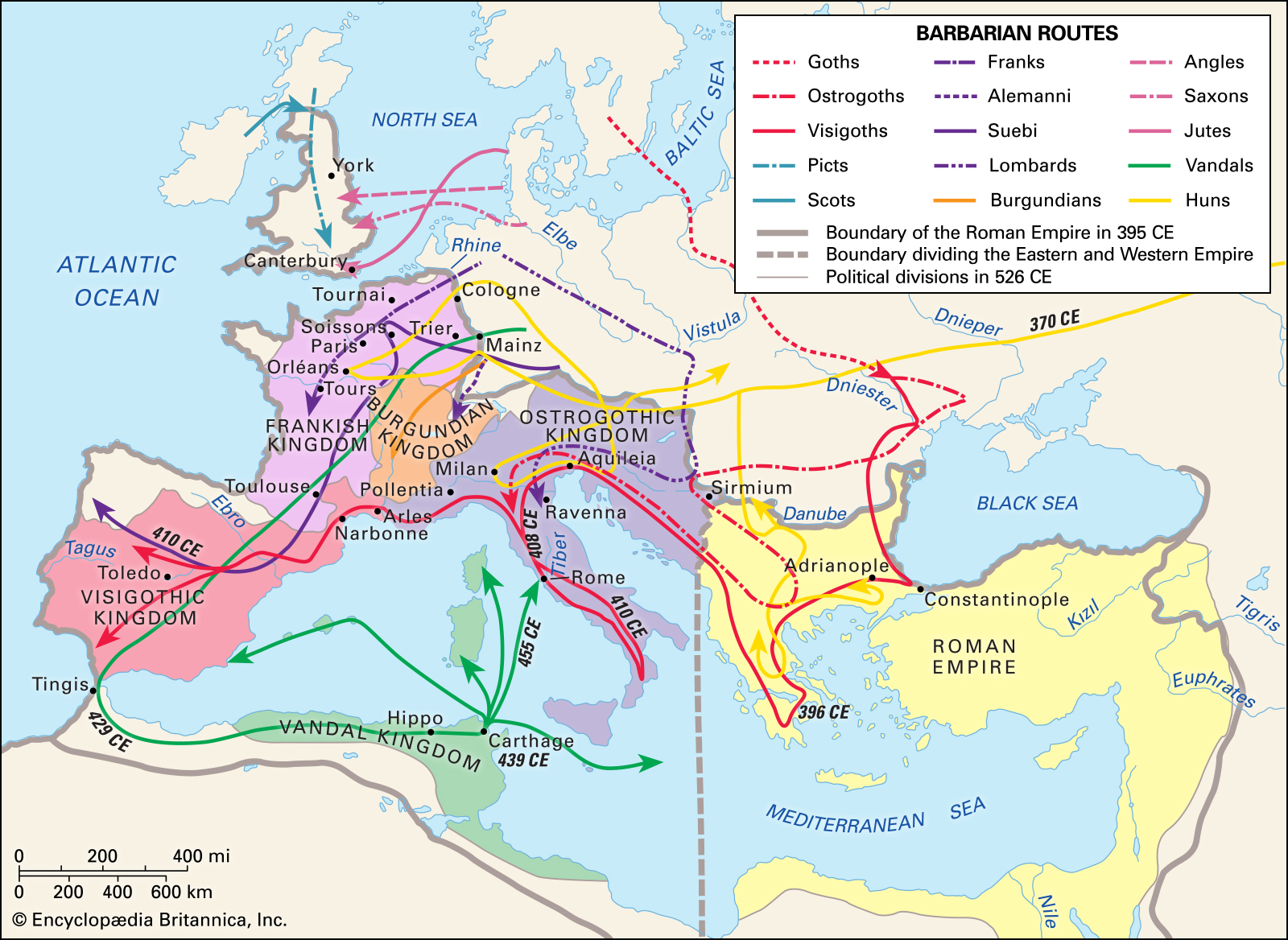

The Burgundians were a Scandinavian people whose original homeland lay on the southern shores of the Baltic Sea, where the island of Bornholm (Burgundarholm in the Middle Ages) still bears their name. About the 1st century CE they moved into the lower valley of the Vistula River, but, unable to defend themselves there against the Gepidae, they migrated westward to the borders of the Roman Empire. There, serving as foederati, or auxiliaries, in the Roman army, they established a powerful kingdom, which by the early 5th century extended to the west bank of the Rhine River and later centred on Sapaudia (Savoy) near Lake Geneva.

As Rome’s hold over the Western Empire declined in the second half of the 5th century, the Burgundians gradually spread their control over areas to the north and west of Savoy and then throughout the Rhône and Saône river valleys. This second Burgundian kingdom reached its zenith under the lawgiver and Christian king Gundobad (474-516), who promulgated a written code of laws, the Lex Gundobada, for the Burgundians and a separate code, the Lex Romana Burgundionum, for his Gallo-Roman subjects. This Burgundy remained independent until 534, when the Franks occupied the kingdom, extinguishing the royal dynasty.

, historical region of France.jpg)

Burgundy (Bourgogne), historical region of France. |

|

|

| |

|

With the death of the Frankish king Clotar I in 561, however, the Frankish kingdom was partitioned among members of the Merovingian dynasty, and one of Clotar’s sons, Guntram, secured the regnum Burgundiae, or kingdom of Burgundy. This kingdom eventually included not only all the former Burgundian lands but also the diocese of Arles in Provence, the Val d’Aosta east of the Alps, and even extensive territory in north-central France. It remained a separate Merovingian kingdom until Charles Martel, the grandfather of Charlemagne, subjugated it to Frankish Austrasia early in the 8th century.

The Carolingians made several partitions of Burgundy before Boso, ruler of the Viennois, had himself proclaimed king of all Burgundy from Autun to the Mediterranean Sea in 879. The French Carolingians later recovered the country west of the Saône and north of Lyons from him, and the German Carolingians recovered Jurane, or Upper, Burgundy (i.e., Transjurane Burgundy, or the country between the Jura and the Alps, together with Cisjurane Burgundy, or Franche-Comté). Boso and his successors, however, were able to maintain themselves in the kingdom of Provence, or Lower Burgundy, until about 933.

In 888 Rudolf I (died 912) of the German Welf family was recognized as king of Jurane Burgundy, including much of what is now Switzerland. His son and successor, Rudolf II, was able to conclude a treaty about 931 with Hugh of Provence, successor of Boso’s son Louis the Blind, whereby he extended his rule over the entire regnum Burgundiae except the areas west of the Saône. This union of Upper and Lower Burgundy was bequeathed in 1032 to the German king and emperor Conrad II and became known from the 13th century as the kingdom of Arles—the name Burgundy being increasingly reserved for the county of Burgundy (Cisjurane Burgundy) and for the duchy of Burgundy.

The duchy of Burgundy was that part of the regnum Burgundiae west of the Saône River; it was recovered from Boso by the French Carolingians and remained a part of the kingdom of France. Boso’s brother Richard, count of Autun, organized the greater part of the territory under his own authority. His son Rudolph (Raoul), who succeeded him in 921, was elected king of France in 923. On Rudolph’s death in 936 the Carolingian king Louis IV and Hugh the Great, duke of the Franks, detached Sens, Troyes, and (temporarily) Langres from Burgundy.

The duchy thus formed, though smaller than its 10th-century predecessor, was stronger and remained in the Capetian family until 1361. In their foreign policy the Capetian dukes adhered loyally to their cousins the kings of France and in internal affairs enlarged their domain and enforced obedience from their vassals. Burgundy came to be recognized as the premier peerage of the French kingdom.

Both the duchy of Burgundy and Cisjurane Burgundy (the county of Burgundy) flourished during this period. The towns prospered: Dijon became an important market town. Pilgrims flocked to Vézelay and Autun, where in 1146 a magnificent church was built around the tomb of St. Lazare. Burgundian monasteries were famous: Cluny (founded 910) became the centre of an order of monks extending from England to Spain, and in 1098 the monastery of Cîteaux was founded and with it a new religious order, the Cistercians.

A reunification of the two Burgundies was effected in 1335 and ended in 1361. The king of France, John II (the Good), reunited the duchy with the domain of the crown, while Cisjurane Burgundy, or Franche-Comté, went to the independent count of Flanders. A new period of Burgundian ducal history began under John II, who in 1363 gave the duchy to his son Philip, who became Philip II, known as “the Bold.” In 1369 Philip married the heiress of the county, Margaret of Flanders. In 1384, when his father-in-law died, Philip inherited Nevers, Rethel, Artois, and Flanders, as well as Franche-Comté. The two Burgundies formed the southern part of a state, the northern possessions of which extended over the Netherlands, the valley of the Meuse, and the Ardennes. In the north, expansion was to continue (Hainaut, 1428; Brabant, 1430; Luxembourg, 1443), but the south, from which Nevers was again detached in 1404, became less and less important. Philip II, however, who lived in Burgundy, did purchase the southern territory of Charolais in 1390.

John the Fearless succeeded Philip II in 1404 and devoted himself to the struggle with his rival Louis, duc d’Orleans, and with Louis’s supporters under the count of Armagnac, who devastated the southern borders of Burgundy between 1412 and 1435. John was assassinated in 1419, and his son Philip III (the Good) continued the struggle against the Armagnacs and threw his support to the English during the Hundred Years’ War. The Treaty of Arras (1435), which established peace between Burgundy and Charles VII of France, added greatly to the Burgundian domain. Even so, mercenary bands continued their depredations in Burgundy until 1445, after which the duchy enjoyed peace until Philip III’s death in 1467.

The next duke, Charles the Bold, was constantly in conflict with the French king Louis XI. Charles’s aim was to unite the northern and southern sections of the kingdom by annexing Lorraine, and he demanded from the Holy Roman emperor the title of king of Burgundy. Charles was thwarted in these efforts by the persistent efforts of Louis XI, who conducted several campaigns against him and subjected Burgundy to an economic blockade.

The two Burgundies suffered from the ravages of the Black Death in 1348 and from the mercenaries’ bands of the Hundred Years’ War. The population declined perceptibly, and this put a heavy strain on production in the 15th century. The lucrative trade in grain, wines, and finished wool was threatened, and the market-fairs lost some of their importance. But on the whole the two Burgundies seem to have enjoyed more security than much of Europe during the 14th and 15th centuries.

After the death of Charles the Bold in 1477, his heiress, Mary of Burgundy, married the Austrian archduke Maximilian of Habsburg (later the Holy Roman emperor), thus disappointing French hopes that she would marry Louis XI’s son Charles, the future Charles VIII of France. The Treaty of Arras (1482), however, ceded Franche-Comté to Charles on his betrothal to Mary’s daughter Margaret of Austria. When he broke this engagement, he had to cede Franche-Comté to Austria by the Treaty of Senlis in 1493.

For the next 185 years Franche-Comté was a possession of the Habsburgs. By the Treaty of Saint-Jean-de-Losne (1522) with France, the neutrality of the county was ensured during the wars between the Habsburgs and the last French kings of the Valois line. Its enduring prosperity, enhanced by industrial development, can be judged by the splendid Renaissance architecture of its towns. Civil disturbances, however, came with the Reformation, when bands of Protestants entered the mainly Roman Catholic county from Germany and Switzerland. Franche-Comté passed to the Spanish Habsburgs through the emperor Charles V’s partition of his dominions in 1556. Under Philip II of Spain a forceful repression of Protestants took place, and Henry IV of France, in his war with Philip, violated Franche-Comté’s neutrality. From 1598 to 1635 peace was maintained, but French fear of Habsburg encirclement led Louis XIII to attempt to annex the county. He invaded and ravaged the area annually from 1636 to 1639, but the Peace of Westphalia (1648) confirmed Habsburg control.

Conquered in 1668 by the Great Condé in the War of Devolution but returned to Spain by the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle (May 2, 1668), Franche-Comté was finally conquered for France by Condé in the last of the so-called Dutch Wars, the French annexation being recognized by the Peace of Nijmegen in 1678. Louis XIV moved the capital of the new province to the former imperial city of Besançon. In 1790, along with the rest of France, Franche-Comté was divided into separate départements—Jura, Doubs, and Haute-Saône.

After the death of Charles the Bold (1477), the duchy of Burgundy was annexed by the French crown. During the 16th century it was devastated by the Wars of Religion. The towns had to be fortified, and mercenaries roamed the country. The duchy was again ravaged in the Thirty Years’ War and also during the aristocratic revolt known as the Fronde (1648–53) led by the Great Condé. Not until the French annexation of Franche-Comté in 1678 were peace and security restored. From 1631 to 1789 the duchy was governed by the princes de Condé. After the French Revolution the province of Burgundy disappeared, divided into the départements of Côte-d’Or, Saône-et-Loire, and Yonne. In 2016 the région of Burgundy was merged with Franche-Comté as part of a national plan to increase bureaucratic efficiency. |

.png)

in 1477 marked in yellow.png)

, historical region of France.jpg)