THE PANTHEON

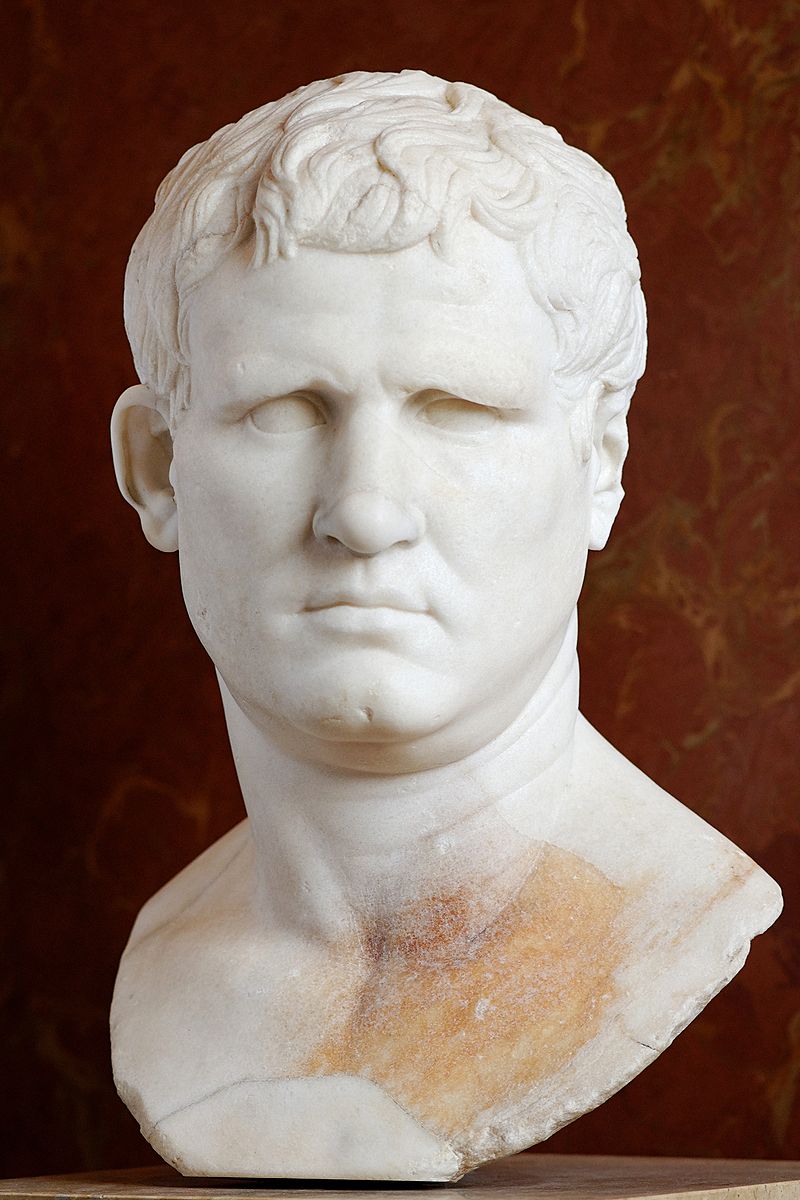

Bust of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa from the Forum of Gabii, currently in the Louvre, Paris.

Bust of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa from the Forum of Gabii, currently in the Louvre, Paris.

|

|

|

| |

|

This incomparable circular edifice, originally intended by Agrippa to form the conclusion of his thermæ [Warm baths which were destined for public use only], with which it is intimately connected, is one of the noblest and most perfect productions of that style of architecture specifically denominated Roman. When the first wonderful creation of this species came into existence, the founder of this glorious dome appears to have himself shrunk back from it, and to have felt that it was not adapted to be the every-day residence of men, but to be a habitation for the gods.

The Church of S. Maria ad Martyres was originally the sudatorium, or sweating-room, of the baths of Agrippa, being similar in construction to all the sweating-rooms now existing, notably one in the Villa of Hadrian at Tivoli. It exactly answers Vetruvius's description of this department of the baths. It seems afterwards to have been dedicated as a temple of the gods, or Pantheon of the Julian line, according to Dion Cassius (liii. 27), when the portico was added in the third consulship of Agrippa.

M. AGRIPPA . L. F. COS . TERTIUM . FECIT.

The straight vertical joint where the Greek portico has been built up to the Roman body can be distinctly seen, and the pediment and entablature can be observed behind the portico. It was burned in the fire under Titus; and was restored, as the inscription on the architrave tells us, by Septimius Severus and Caracalla—

PANTHEUM VETUSTATE CORRUPTUM CUM OMNI CULTU RESTITVERUNT.

Recent explorations have shown that in front of the Pantheon was a large enclosure surrounded by a covered arcade, somewhat after the manner of the colonnade at S. Peter's, and entered by an arch of triumph. Remains of this arch exist under the houses in front of the Pantheon, which are to be pulled down.

When Agrippa dedicated the Pantheon as a temple, it was consecrated to Jupiter the Avenger. "Some of the finest works that the world has ever beheld ... the roofing of the Pantheon of Jupiter Ultor that was built by Agrippa" (Pliny, "N. H." xxxvi. 24). The repairs commenced by Septimius Severus and Caracalla were completed by Alexander Severus, who built his baths close by. We call attention to a coin of this emperor, which represents the temple and its enclosure on the reverse; on the obverse is the emperor's portrait, and the legend IMP . C . M . AVR . SEV . ALEXANDER . AUG. On the coin the columns are placed close on either flank, and two are omitted, to show the seated statue of Jupiter in the temple, which statue is now in the Hall of Busts in the Vatican Museum, and is a copy of the celebrated Jupiter of Phidias.

The fact that the Pantheon was originally built as a sudatorium has been proved to a certainty by the excavations made in the sudatorium of the Baths of Caracalla. There we have, as it were, the Pantheon in ruins. It is slightly smaller, the diameter being 125 feet—17 less than the Pantheon. Opposite to the entrance is an apse, and on each side there are three recesses, as at the Pantheon, which were used as caldaria, but are now, in the Pantheon, chapels of the saints.

Das Pantheon und die Piazza della Rotonda in Rom, 1836. (An 1836 view of the Pantheon by Jakob Alt, showing twin bell towers, often misattributed to Bernini.)

(W)

Das Pantheon und die Piazza della Rotonda in Rom, 1836. (An 1836 view of the Pantheon by Jakob Alt, showing twin bell towers, often misattributed to Bernini.)

(W) |

The portico is 110 feet long, and 44 feet deep. Sixteen Corinthian columns, 46½ feet high and 5 feet in diameter, support the roof. The Pantheon was converted into a church by Boniface IV. in 609, by permission of the Emperor Phocas, and it was dedicated to the martyrs on November 1st (All Saints' Day), 830. The doors and grating above, of ancient bronze, with the rim round the circular opening in the vault of the interior, are all that is left of the ancient metal work. The interior is 142 feet in diameter, and 143 feet high, and is lighted by an open space of 28 feet in diameter. It is the burial-place of Raphael and of Victor Emanuel II.—right of high altar.

Pliny says ("Nat. Hist." xxxvi. 4): "The Pantheon of Agrippa has been decorated by Diogenes of Athens, and the caryatides by him, which form the columns of that temple, are looked upon as masterpieces of excellence. The same, too, with the statues that are placed upon the roof, though, in consequence of the height, they have not had an opportunity of being so well appreciated." "The capitals, too, of the pillars which were placed by M. Agrippa in the Pantheon, were made of Syracusan metal" (ibid., xxxiv. 7). Marcellinus (xvi. x. 14) says: "The Pantheon, with its vast extent, its imposing height, and the solid magnificence of its arches, and the lofty niches rising one above the other like stairs, is adorned with the images of former emperors."

Einblick Panorama Pantheon, Rom. Einblick Panorama Pantheon, Rom. |

"It is as difficult to reconcile the statements of different authors respecting the original idea of Agrippa, as it is hazardous to attempt to prove the successive metamorphoses which the plan sketched by the artist has undergone. This much, however, is certain, that with respect to the modern transformation of the whole, the consequences have been most melancholy and injurious. The combination of the circular edifice with the rectilinear masses of the vestibule, notwithstanding all the pains bestowed, and the endless expenditure of the most costly materials, has been unsuccessful; and the original design of the Roman architect has lost much of its significance, or, at all events, of its phrenological expression, by being united with ordinary Grecian forms of architecture, which in this place lose great part of their value. No one previously unacquainted with the edifice could form an idea, from the aspect of the portico, of that wondrous structure behind, which must ever be considered as one of the noblest triumphs of the human mind over matter in connection with the law of gravity.

"Conflagrations, earthquakes, sacrilegious human hands, and all the injuries of time, have striven together in vain for the destruction of this unique structure. It has come off victorious in every trial; and even now, when it has not only been stripped of its noblest decorations, but, what is still worse, been decked out with idle and unsuitable ornaments, it still stands in all its pristine glory and beauty.

"In order to obtain a notion of the size and solid excellence of the work, it will be well first to make the circuit of the entire edifice. We shall thus have an opportunity of admiring the fine distribution of the different masses. After the first circular wall or belt, which rests upon a base of travertine, has attained a height of nearly forty feet, it is finished off with a simple cornice, serving as a solid foundation for the second belt. As a preservative against sinking, this is, moreover, provided with a series of larger and smaller construction arches, alternating symmetrically with one another. After rising some thirty feet, further solidity is given to the wall by a girdle suitably decorated with consoles, and on this the third belt (which is but a few feet lower) is supported. A similar number of the arches already mentioned, introduced as frequently as possible, enables this wall to support the weight pressing upon it, and to raise the harmoniously rounded cupola boldly aloft.

Rom, Pantheon bei Nacht. (W) Rom, Pantheon bei Nacht. (W) |

"In ancient times the whole building, which is composed of brick, was covered and embellished with a coating of stucco. On the upper cornice, at the back, between the consoles, portions of terra-cotta decorations still remain, seeming to have formed part of this ornamental facing.

"In our examination of the interior, we are, unfortunately, much hindered in our attempt to investigate the constructive connection of the whole by the unmeaning ornamental additions, and the thoughtless transformation of the different organic masses.

"So much, however, may be discovered even on a superficial survey—namely, that the architect has everywhere endeavoured, not merely to diminish the pressure on the walls of the lower belt (which is nearly twenty feet thick) by inserting hollow chambers, but has given them additional strength by means of the vaulted constructions thus introduced. A hall, supported on pillars, lies between each of the eight modern altars, and behind each of them, on the outside, are niches, reached through the different doors, recurring at regular distances throughout.

"The slabs of coloured marble belonging to the attica were carried off some hundred years ago, under Benedict XIV., and their place supplied by the present coulisse paintings. This polychrome system would have greatly facilitated our researches into the coloured architecture of the ancients, and its loss is therefore much to be regretted.

"For, although this portion of the edifice was thus transformed at a comparatively late period, still the effect of those finely harmonized masses must have been a remarkable one.

"To judge from the combination of coloured stones still remaining in this edifice, the effect must have been very rich and beautiful. The elaborate capitals and bases of white marble must have formed a fine contrast to the yellow shafts of the pillars and the stripe of porphyry inserted in the architrave. The largest specimen of this coloured mode of decoration has been preserved in the pavement; although here also we must take it for granted that the original arrangement has been disturbed, the sunken bases of the columns sufficing to prove that the pavement has been raised in course of time. This circumstance is not without optical reaction on the proportions of the different masses. The horse-shoe arch over the entrance-door is remarkable. It forms a striking contrast to that of the tribune, where the projecting cornice rests upon two pillars, whereas the architrave, broken through by the doorway, is supported only by pilasters.

"The ædiculæ, now converted into altars, are covered in, partly with gables, partly with arches, the former resting upon fluted pillars of yellow marble, the latter upon porphyry pillars. The walls behind are likewise faced with slabs of coloured marble, which, in their original splendour, must have reflected the magnificence of the pillars.

"The facing of the door is the only considerable portion still remaining of the rich bronze-work with which this edifice was formerly fitted up. Simple as the decoration of these massive doors now appears, it is yet imposing for such persons as are capable of appreciating pure symmetry and a judicious distribution of the parts in surfaces so extensive. The nails, with heads in the form of rosettes, separating the different panels, are the only ornament. The window above the door is closed by a grating composed of curves placed one above the other, thus admitting both light and air. The destruction of the bronze cross-beams which formed the roof of the vestibule till the time of Urban VIII., is most to be regretted. This was composed of bronze tubes, on precisely the same principle as that on which Stephenson, a few years ago, constructed the bridge over the Menai Straits.

"The cupola is nearly seventy feet in height, and rests on the attica, corresponding to the second outer belt. This attica has suffered most severely from modern alterations. The walls behind this afford space for a series of chambers. The massive wall of the third belt, on the other hand, surrounding the cupola to a third of its height, is rendered accessible by a passage running round the whole; and this again is spanned by frequently recurring arches, and lighted by the windows visible on the outside.

"The diameter of the cupola is nearly equal to its height. The round aperture at the top, by means of which the interior is lighted with a magical effect, measures about twenty-eight feet in diameter. Here is still to be seen the last and only remnant of the rich bronze decorations of which this edifice formerly boasted. It consists of a ring, adorned with eggs and foliage, encircling the aperture, and not merely strengthening the edge of the wall, but constituting a graceful and at the same time a simple and judicious ornament.

"It is certain that the five converging rows of gradually diminishing cassettoni have been decorated in a similar manner, and it is stated that vestiges of metal were discovered during the process of whitewashing.

"The six niches between the altars are each supported by two fluted pillars and a corresponding number of pilasters, the greater portion of them being composed of monoliths of that costly yellow marble frequently employed by the ancients. They are more than thirty-two feet in height, and, as regards size, are unique of their kind. It has been impossible, even for the ancients, to erect, of this rare material, all the pillars required for the embellishment of this splendid edifice, for which reason they were obliged to substitute six of pavonazzetto. These, however, they stained, without injuring the brilliancy of the marble or the transparency of the grain, in such a manner as to bring them into harmony with the other yellow masses, and to deceive even the most practised eye. This circumstance is of great importance in forming an opinion on the coloured architecture of the Greeks, as it shows how they contrived to harmonize the white marble masses without concealing the texture of the noble material.

"It is stated by Pliny that caryatides were placed here by a certain Diogenes of Athens, corresponding to the pillars which support the architrave.

"Apparently they were a free repetition of the caryatides of the Pandrosium; and probably the statue in the Braccio Nuovo, which was brought from the Palazzo Paganica, in the immediate neighbourhood of the Pantheon, was one of these, the scale being precisely adapted to this situation.

"Some of the large nails used in riveting the bronze plates together are still preserved in the different museums. We are indebted to Serlio, an architect of the sixteenth century, who preserved a drawing of it, for the only information we possess concerning this ingenious piece of mechanism. The Pope mentioned above, a member of the Barberini family, had the barbarity to carry off and melt down these important remains. An inscription on the left of the principal door celebrates the judicious transformation of these masses of bronze into cannons, and ornaments for churches" (Braun).

Urban VIII. "That the useless and almost forgotten decorations might become ornaments of the apostle's tomb in the Vatican temple, and engines of public safety in the fortress of S. Angelo, he moulded the ancient relics of the bronze roof into columns and cannons, in the twelfth year of his pontificate" (Inscription).

"What the barbarians did not the Barberini have done" (Pasquino).

"On each side of the entrance to the Rotunda are two immense niches, constructed of brick, in which the colossal statues of Augustus and Agrippa are supposed to have been placed. This opinion seems to me too hazardous, and contrary to the spirit of these two eminent statesmen.

"Standing among the sixteen granite pillars supporting the vestibule, we feel that there is something overpowering in the impression it produces. This, however, diminishes when we step out upon the piazza, which lies too high. At its original level, a flight of five steps led up to the building; and the effect when viewed from a distance must have been essentially different, as we may judge from the portion of pavement which has been excavated to the right of the Rotunda" (Braun).

Raphael's tomb is in the third chapel on the left.

“Living, great Nature feared he might outvie

Her works; and, dying, fears herself to die.”

| — Cardinal Bembo: translated by Pope. |

A bust, by Nardini, of Raphael was originally placed near here, but was removed in 1820, in consequence of people offering their devotions to it.

|