- Roma imparatorluk topraklarında evrensel olarak dinsel hoşgörü ilkesini uyguladı ve Yahudileri de geleneklerini izlemede özgür bıraktı.

- Yahudiler etnik inançları gereği Roma egemenliğine karşı hoşgörüsüz davrandılar.

- Helenistik kültüre ve Roma egemenliğine karşı bir Yahudi Krallığının kurulması savaşımında kurtarıcı Mesih motifi birincil devrimci dürtü oldu.

- İsa’nın gelişinden önce, Judea’da çok sayıda yeni “mesih” önderliğinde Roma egemenliğine karşı ayaklanmalar ve gerilla savaşları görüldü. Roma Yahudi tapınağını yerle bir etti.

- Seçilmiş halk olarak ve bir gentile okyanusu tarafından kuşatılı etnik kültür olarak, Yahudilik sürekli bir kurtarıcı Mesih (“the anointed one”) bekleyişi içinde idi.

|

|

ROMA VE JUDEA

Relations between Jews and the Roman Empire (B)

In the 1st century Rome showed no interest in making the Jews in Palestine and other parts of the empire conform to common Greco-Roman culture. A series of decrees by Julius Caesar, Augustus, the Roman Senate, and various city councils permitted Jews to keep their own customs, even when they were antithetical to Greco-Roman culture. For example, in respect for Jewish observance of the Sabbath, Rome exempted Jews from conscription in Rome’s armies. Neither did Rome colonize Jewish Palestine. Augustus established colonies elsewhere (in southern France, Spain, North Africa, and Asia Minor), but prior to the First Jewish Revolt (AD 66-74) Rome established no colonies in Jewish Palestine. Few individual Gentiles from abroad would have been attracted to live in Jewish cities, where they would have been cut off from their customary worship and cultural activities. The Gentiles who lived in Tiberias and other Jewish cities were probably natives of nearby Gentile cities, and many were Syrians, who could probably speak both Aramaic and Greek. |

First Jewish Revolt

AD 66-70 (W)

First Jewish Revolt, (AD 66-70), Jewish rebellion against Roman rule in Judaea.

The First Jewish Revolt was the result of a long series of clashes in which small groups of Jews offered sporadic resistance to the Romans, who in turn responded with severe countermeasures. In the fall of AD 66 the Jews combined in revolt, expelled the Romans from Jerusalem, and overwhelmed in the pass of Beth-Horon a Roman punitive force under Gallus, the imperial legate in Syria. A revolutionary government was then set up and extended its influence throughout the whole country. Vespasian was dispatched by the Roman emperor Nero to crush the rebellion. He was joined by Titus, and together the Roman armies entered Galilee, where the historian Josephus headed the Jewish forces. Josephus’ army was confronted by that of Vespasian and fled. After the fall of the fortress of Jatapata, Josephus gave himself up, and the Roman forces swept the country.

Triumphal parade in Rome of Jewish religious articles (a seven-branched candlestick, a table for shewbread, and sacred trumpets) removed after the sack of Jerusalem in 70 ce; detail of reliefs from the Arch of Titus, Rome, 81 CE. |

On the 9th of the month of Av (August 29) in AD 70, Jerusalem fell; the Temple was burned, and the Jewish state collapsed, although the fortress of Masada was not conquered by the Roman general Flavius Silva until April 73. |

|

Messiah (B)

Messiah, (from Hebrew mashiaḥ, “anointed”), in Judaism, the expected king of the Davidic line who would deliver Israel from foreign bondage and restore the glories of its golden age. The Greek New Testament’s translation of the term, christos, became the accepted Christian designation and title of Jesus of Nazareth, indicative of the principal character and function of his ministry. More loosely, the term messiah denotes any redeemer figure; and the adjective messianic is used in a broad sense to refer to beliefs or theories about an eschatological improvement of the state of humanity or the world.

The biblical Old Testament never speaks of an eschatological messiah, and even the “messianic” passages that contain prophecies of a future golden age under an ideal king never use the term messiah. Nevertheless, many modern scholars believe that Israelite messianism grew out of beliefs that were connected with their nation’s kingship. When actual reality and the careers of particular historical Israelite kings proved more and more disappointing, the “messianic” kingship ideology was projected on the future.

After the Babylonian Exile, Jews’ prophetic vision of a future national restoration and the universal establishment of God’s kingdom became firmly associated with their return to Israel under a scion of David’s house who would be “the Lord’s anointed.” In the period of Roman rule and oppression, the Jews’ expectation of a personal messiah acquired increasing prominence and became the centre of other eschatological concepts held by various Jewish sects in different combinations and with varying emphases. In some sects, the “son of David” messianism, with its political implications, was overshadowed by apocalyptic notions of a more mystical character. Thus some believed that a heavenly being called the “Son of Man” (the term is derived from the Book of Daniel) would descend to save his people. The messianic ferment of this period, attested by contemporary Jewish-Hellenistic literature, is also vividly reflected in the New Testament. With the adoption of the Greek word Christ by the church of the Gentiles, the Jewish nationalist implications of the term messiah (implications that Jesus had explicitly rejected) vanished altogether, and the “Son of David” and “Son of Man” motifs could merge in a politically neutral and religiously highly original messianic conception that is central to Christianity. |

Messianic views (B)

The traditional Jewish view of the fulfillment of the history of salvation was guided by the idea that at the end of history the messiah will come from the house of David and establish the Kingdom of God — an earthly kingdom in which the Anointed of the Lord will gather the tribes of the chosen people and from Jerusalem will establish a world kingdom of peace. Accordingly, the expectation of the Kingdom had an explicitly inner-worldly character. The expectation of an earthly messiah as the founder of a Jewish kingdom became the strongest impulse for political revolutions, primarily against Hellenistic and Roman dominion. The period preceding the appearance of Jesus was filled with uprisings in which new messianic personalities appeared and claimed for themselves and their struggles for liberation the miraculous powers of the Kingdom of God. Especially in Galilee, guerrilla groups were formed in which hope for a better future blazed all the more fiercely because the present was so unpromising.

| Jesus disappointed the political expectations of those popular circles; he did not let himself be made a political messiah. Conversely, it was his opponents who used the political misinterpretation of his person to destroy him. Jesus was condemned and executed by the Roman authorities as a Jewish rioter who rebelled against Roman sovereignty. The inscription on the cross, “Jesus of Nazareth, king of the Jews,” cited the motif of political insurrection of a Jewish messianic king against the Roman government as the official reason for his condemnation and execution |

|

|

|

|

|

|

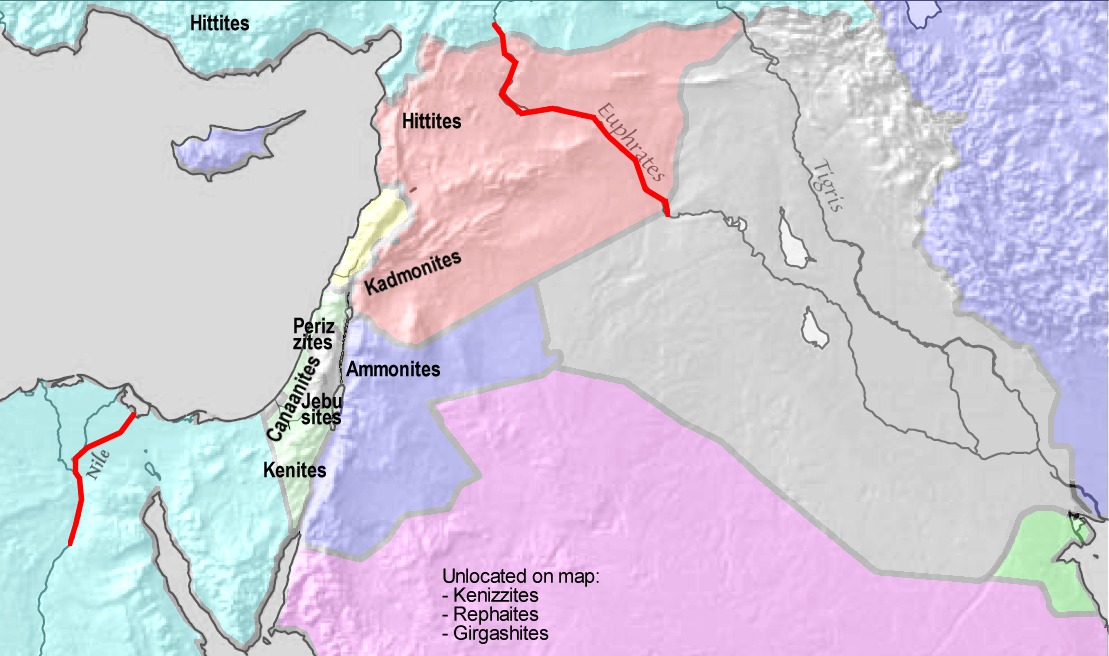

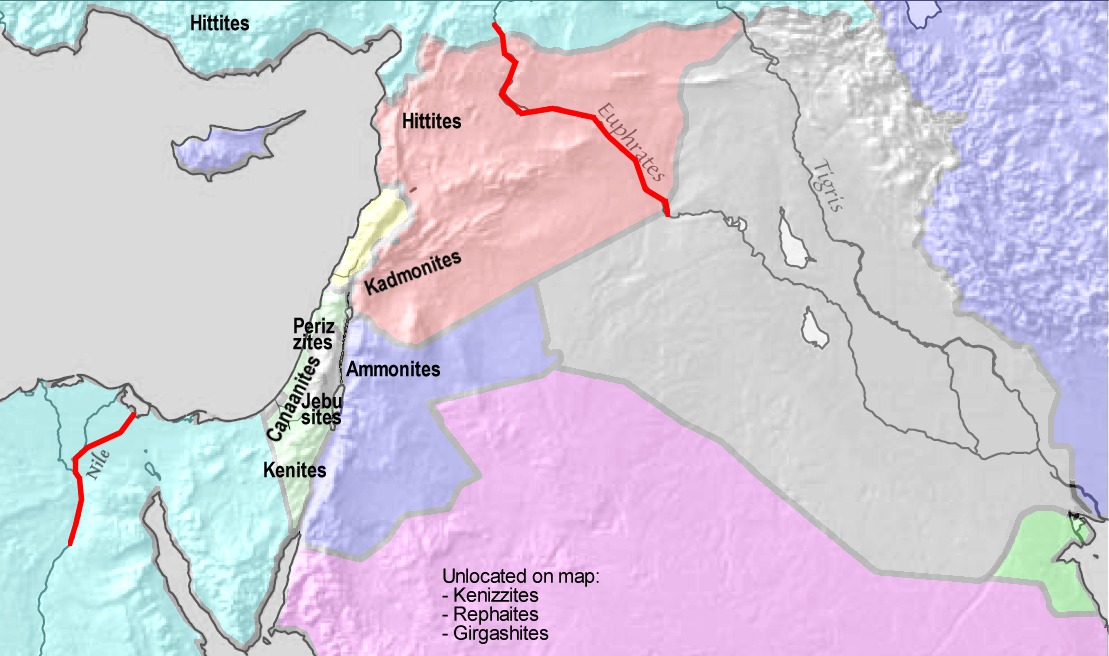

The boundaries of the region which was promised to Abraham's descendants in the covenant of the pieces as defined in Genesis 15:18-21. |

|

|

|

Abraham

Abraham (W)

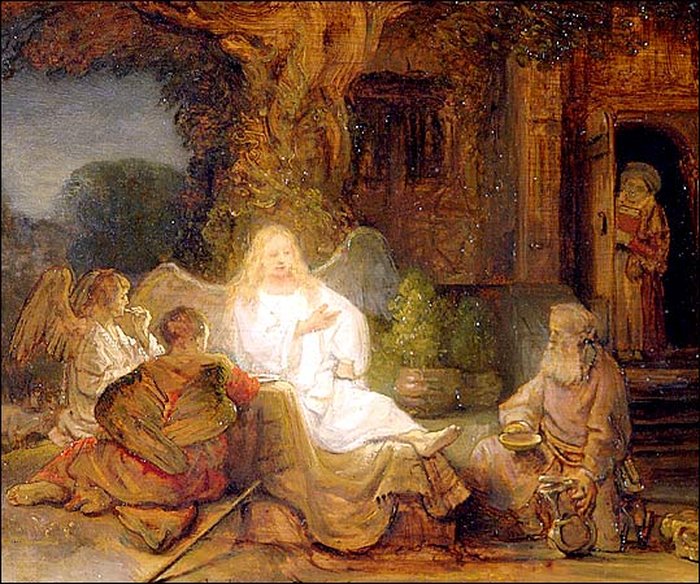

Abraham Serving the Three Angels by Rembrandt |

Abraham, originally Abram, is the common patriarch of the three Abrahamic religions. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the Covenant, the special relationship between the Jewish people and God; in Christianity, he is the prototype of all believers, Jewish or Gentile; and in Islam he is seen as a link in the chain of prophets that begins with Adam and culminates in Muhammad.

The narrative in Genesis revolves around the themes of posterity and land. Abraham is called by God to leave the house of his father Terah and settle in the land originally given to Canaan but which God now promises to Abraham and his progeny.

The Abraham story cannot be definitively related to any specific time, and it is widely agreed that the patriarchal age, along with the exodus and the period of the judges, is a late literary construct that does not relate to any period in actual history. A common hypothesis among scholars is that it was composed in the early Persian period (late 6th century BCE) as a result of tensions between Jewish landowners who had stayed in Judah during the Babylonian captivity and traced their right to the land through their "father Abraham", and the returning exiles who based their counter-claim on Moses and the Exodus tradition. |

Covenant of the pieces (W)

According to the Hebrew Bible, the covenant of the pieces or covenant between the parts (Hebrew: ברית בין הבתרים berith bayin hebatrim) was an event in which God revealed himself to Abraham and made a covenant with him, in which God announced to Abraham that his descendants would eventually inherit the Land of Israel. This was the first of a series of covenants made between God and the biblical patriarchs.

Yahweh declared all of the regions of land that Abram's offspring would claim:

"In that day the LORD made a covenant with Abram, saying: 'Unto thy seed have I given this land, from the river of Egypt unto the great river, the river Euphrates; the Kenite, and the Kenizzite, and the Kadmonite, and the Hittite, and the Perizzite, and the Rephaim, and the Amorite, and the Canaanite, and the Girgashite, and the Jebusite.'

|

The covenant found in Genesis 12-17 is known in Hebrew as the Brit bein HaBetarim, the “Covenant Between the Parts,” and is the basis for brit milah (covenant of circumcision) in Judaism. The covenant was for Abraham and his seed, or offspring, both of natural birth and adoption.

... In Genesis 12 and 15, God grants Abram land and descendants but does not place any stipulations (unconditional). By contrast, Gen. 17 contains the covenant of circumcision (conditional).

- To make of Abraham a great nation and to bless those who bless him and curse those who curse him and all peoples on earth would be blessed through Abraham.[Gen 12:1-3]

- To give Abraham's descendants all the land from the river (or wadi) of Egypt to the Euphrates.[Gen 15:18–21] Later, this land came to be referred to as the Promised Land or the Land of Israel.

- To make Abraham the father of many nations and of many descendants and give "the whole land of Canaan" to his descendants.[Gen 17:2-9]

- Circumcision is to be the permanent sign of this everlasting covenant with Abraham and his male descendants and is known as the brit milah.[Gen 17:9-14]

|

The boundaries of the region which was promised to Abraham's descendants in the covenant of the pieces as defined in Genesis 15:18-21. |

|

|

|

|

Messiah

Messiah (W)

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (Hebrew: מָשִׁיחַ, translit. māšîaḥ; Greek: μεσσίας, translit. messías, Arabic: مسيح, translit. masîḥ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people.

The concepts of moshiach, messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible; a moshiach (messiah) is a king or High Priest traditionally anointed with holy anointing oil. Messiahs were not exclusively Jewish: the Book of Isaiah refers to Cyrus the Great, king of the Achaemenid Empire, as a messiah for his decree to rebuild the Jerusalem Temple.

Ha mashiach (המשיח, “the Messiah,” “the anointed one”), often referred to as melekh mashiach (מלך המשיח "King Messiah"), is to be a human leader, physically descended from the paternal Davidic line through King Davidand King Solomon. He is thought to accomplish predetermined things in only one future arrival, including the unification of the tribes of Israel, the gathering of all Jews to Eretz Israel, the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem, the ushering in of a Messianic Age of global universal peace, and the annunciation of the world to come. The specific expression, "HaMashiach" (המשיח, lit. "the Messiah"), does not occur in the Tanakh.

In Christianity, the Messiah is called the Christ, from Greek: χριστός, translit. khristós, translating the Hebrew word of the same meaning. The concept of the Messiah in Christianity originated from the Messiah in Judaism. However, unlike the concept of the Messiah in Judaism and Islam, the Messiah in Christianity is the Son of God. Christ became the accepted Christian designation and title of Jesus of Nazareth, because Christians believe that the messianic prophecies in the Old Testament were fulfilled in his mission, death, and resurrection. These specifically include the prophecies of him being descended from the Davidic line, and being declared King of the Jews which happened on the day of his Crucifixion.

They believe that Christ will fulfill the rest of the messianic prophecies, specifically that he will usher in a Messianic Age and the world to come at the Second Coming.

In Islam, Jesus was a prophet and the Masîḥ (مسيح), the Messiah sent to the Israelites, and he will return to Earth at the end of times, along with the Mahdi, and defeat al-Masih ad-Dajjal, the false Messiah. |

|

|

|

| In the Book of Joshua, Canaanites are included in a list of nations to exterminate, and later described as a group which the Israelites had annihilated. |

|

Canaan

Canaan (W)

|

Canaan (/ˈkeɪnən/; Northwest Semitic: knaʿn; Phoenician: 𐤊𐤍𐤏𐤍 Kenāʿan; Hebrew: כְּנָעַן Kena‘an) was a Semitic-speaking region in the Ancient Near East during the late 2nd millennium BC. The name Canaan appears throughout the Bible, where it corresponds to the Levant, in particular to the areas of the Southern Levant that provide the main setting of the narrative of the Bible: i.e., the area of Phoenicia, Philistia, Israel, and other nations.

The word Canaanites serves as an ethnic catch-all term covering various indigenous populations—both settled and nomadic-pastoral groups—throughout the regions of the southern Levant or Canaan. It is by far the most frequently used ethnic term in the Bible. In the Book of Joshua, Canaanites are included in a list of nations to exterminate, and later described as a group which the Israelites had annihilated, although this narrative is contradicted by later biblical texts such as the Book of Isaiah. Biblical scholar Mark Smith notes that archaeological data suggests “that the Israelite culture largely overlapped with and derived from Canaanite culture. ... In short, Israelite culture was largely Canaanite in nature.”

The name "Canaanites" (כְּנָעַנִיְם kena‘anim, כְּנָעַנִי kena‘anī) is attested, many centuries later, as the endonym of the people later known to the Ancient Greeks from c. 500 BC as Phoenicians, and following the emigration of Canaanite-speakers to Carthage (founded in the 9th century BC), was also used as a self-designation by the Punics (chanani) of North Africa during Late Antiquity.

Canaan had significant geopolitical importance in the Late Bronze Age Amarna period (14th century BC) as the area where the spheres of interest of the Egyptian, Hittite, Mitanni and Assyrian Empires converged. Much of modern knowledge about Canaan stems from archaeological excavation in this area at sites such as Tel Hazor, Tel Megiddo, and Gezer.

|

|

|

|

|