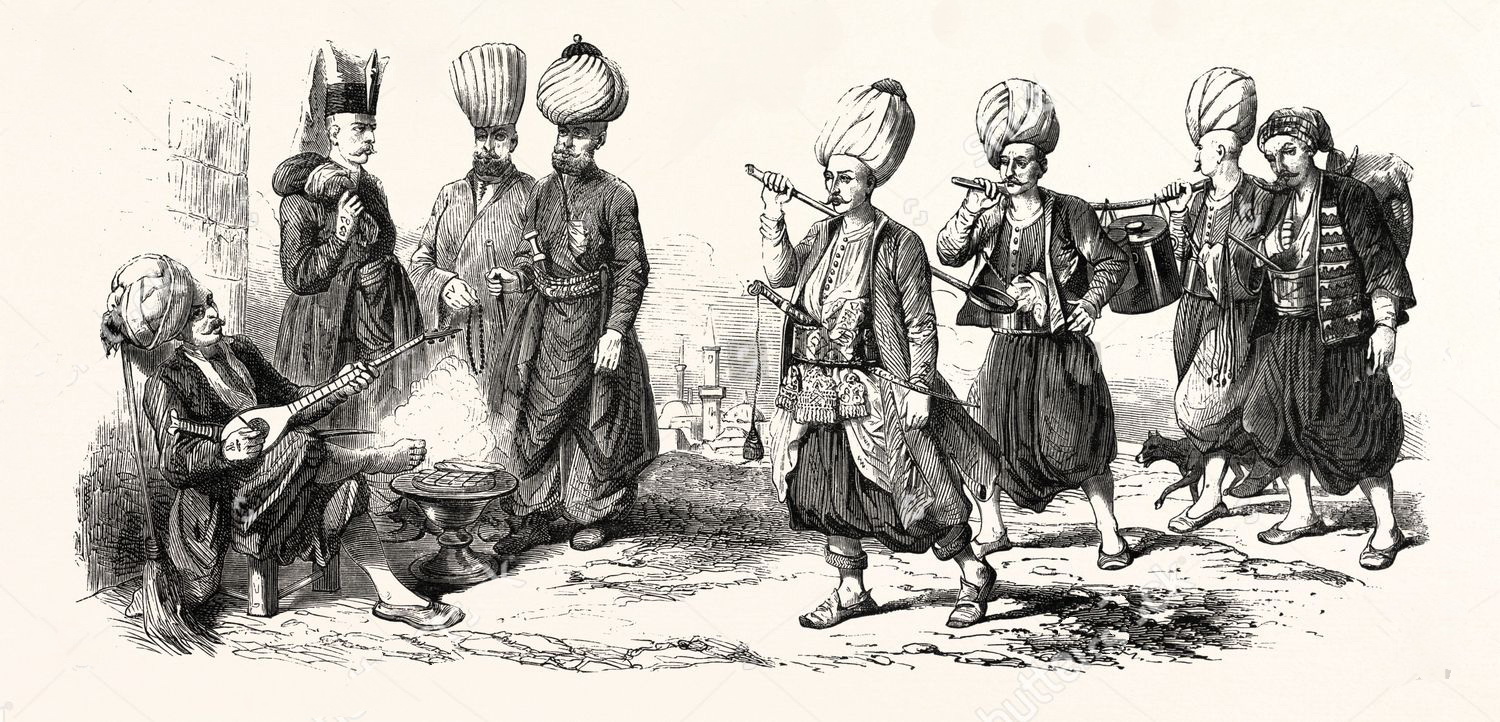

Fashion, clothes, folk costumes in Turkey from 1800-1825, soldiers and women, from the left, a janissary representative, a so-called Jamak, then a maritime soldier, a Peik, a kind of guardsman, a Turkish woman in a veil, a Turkish woman in a house suit, and a janissary, as a companion of the vizier, digital improved reproduction from an original from the year 1900. |

|

|

Janissaries (W)

Janissaries (W)

| Active |

1363-1826 (1830 for Algiers) |

| Allegiance |

Ottoman Empire |

| Type |

Infantry |

| Role |

Standing professional military |

| Size |

1,000 (1400), 7,841 (1484), 13,599 (1574), 37,627 (1609) |

| Part of |

Ottoman army |

| Garrison/HQ |

Adrianople (Edirne), Constantinople (Istanbul) |

| Colors |

Blue, Red and Green |

| Equipment |

Various |

| Engagements |

Battle of Kosovo, Battle of Kriva Palanka, Battle of Nicopolis, Battle of Ankara, Battle of Varna, Battle of Chaldiran, Battle of Mohács, Siege of Vienna, Great Siege of Malta and others |

|

|

| |

|

The Janissaries (Ottoman Turkish: يڭيچرى yeñiçer, meaning “new soldier”) were elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman Sultan’s household troops, bodyguards and the first modern standing army in Europe. The corps was most likely established during the reign of Murad I (1362-1389).

They began as an elite corps of slaves made up of kidnapped young Christian boys who were converted to Islam, and became famed for internal cohesion cemented by strict discipline and order. Unlike typical slaves, they were paid regular salaries. Forbidden to marry or engage in trade, their complete loyalty to the Sultan was expected. By the seventeenth century, due to a dramatic increase in the size of the Ottoman standing army, the corps' initially strict recruitment policy was relaxed. Civilians bought their way into it in order to benefit from the improved socioeconomic status it conferred upon them. Consequently, the corps gradually lost its military character, undergoing a process that has been described as 'civilianization'. The Janissaries were a highly formidable military unit in the early years, but as Western Europe modernized its military organization technology, the Janissaries became a reactionary force that resisted all change. Steadily the Ottoman military power became outdated, but when the Janissaries felt their privileges were being threatened, or outsiders wanted to modernize them, or they might be superseded by the cavalrymen, they rose in rebellion. The rebellions were highly violent on both sides, but by the time the Janissaries were suppressed, it was far too late for Ottoman military power to catch up with the West. The corps was abolished by Sultan Mahmud II in 1826 in the Auspicious Incident, in which 6,000 or more were executed. |

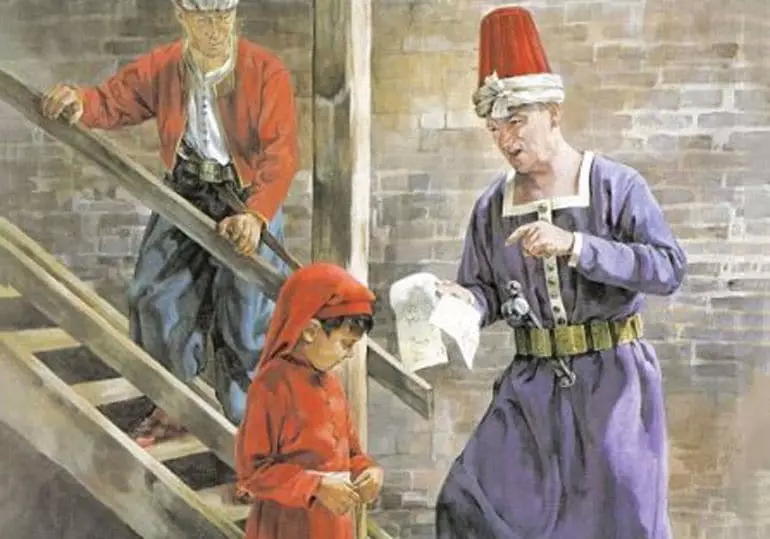

Illustration by Christa Hook. |

|

|

|

| |

Gentile Bellini, “A Turkish Janissary,” c. 1480). |

|

|

|

| |

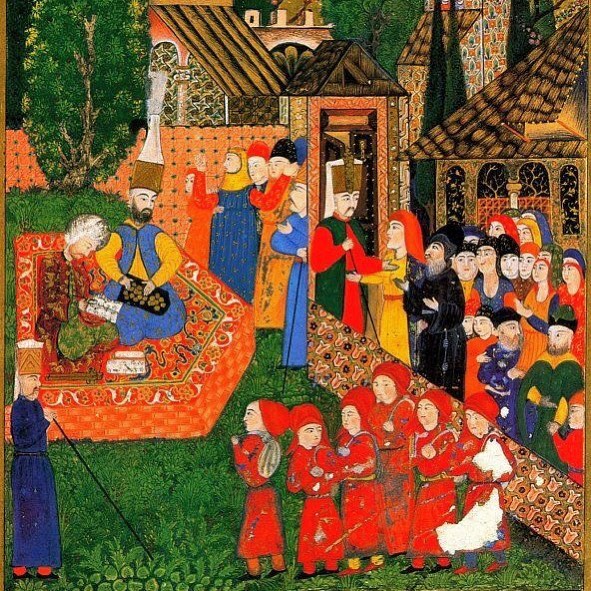

Ottoman Janissaries, training.. |

|

|

|

Origins (W)

The formation of the Janissaries has been dated to the reign of Murad I (r. 1362-1389), the third ruler of the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans instituted a tax of one-fifth on all slaves taken in war, and it was from this pool of manpower that the sultans first constructed the Janissary corps as a personal army loyal only to the sultan.

Illustration of the registration of Christian boys for the devshirme. |

|

|

|

From the 1380s to 1648, the Janissaries were gathered through the devşirme system, which was abolished in 1638. This was the taking (enslaving) of non-Muslim boys, notably Anatolian and Balkan Christians; Jews were never subject to devşirme, nor were children from Turkic families. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, "in early days, all Christians were enrolled indiscriminately. Later, those from Albania, Bosnia, and Bulgaria were preferred.” |

| |

|

The Janissaries were kapıkulları (sing. kapıkulu), "door servants" or "slaves of the Porte," neither freemen nor ordinary slaves (köle). They were subjected to strict discipline, but were paid salaries and pensions upon retirement and formed their own distinctive social class. As such, they became one of the ruling classes of the Ottoman Empire, rivalling the Turkish aristocracy. The brightest of the Janissaries were sent to the palace institution, Enderun. Through a system of meritocracy, the Janissaries held enormous power, stopping all efforts at reform of the military.

According to military historian Michael Antonucci and economic historians Glenn Hubbard and Tim Kane, the Turkish administrators would scour their regions (but especially the Balkans) every five years for the strongest sons of the sultan’s Christian subjects. These boys (usually between the ages of 6 and 14) were then taken from their parents and given to Turkish families in the provinces to learn Turkish language and customs, and the rules of Islam. The recruits were indoctrinated into Islam, forced into circumcision and supervised 24 hours a day by eunuchs. They were subjected to severe discipline, being prohibited from growing a beard, taking up a skill other than soldiering, and marrying. As a result, the Janissaries were extremely well-disciplined troops, and became members of the askeri class, the first-class citizens or military class. Most were non-Muslims, because it was not permissible to enslave a Muslim.

It was a similar system to the Iranian Safavid, Afsharid, and Qajar era ghilmans, who were drawn from converted Circassians, Georgians, and Armenians, and in the same way as with the Ottoman's Janissaries who had to replace the unreliable ghazis. They were initially created as a counterbalance to the tribal, ethnic and favoured interests the Qizilbash gave, which make a system imbalanced.

In the late 16th century, a sultan gave in to the pressures of the Corps and permitted Janissary children to become members of the Corps, a practice strictly forbidden for the previous 300 years. According to paintings of the era, they were also permitted to grow beards. Consequently, the formerly strict rules of succession became open to interpretation. While they advanced their own power, the Janissaries also helped to keep the system from changing in other progressive ways, and according to some scholars the corps shared responsibility for the political stagnation of Istanbul.

Greek Historian Dimitri Kitsikis in his book Türk Yunan İmparatorluğu ("Turco-Greek Empire") states that many Bosnian Christian families were willing to comply with the devşirme because it offered a possibility of social advancement. Conscripts could one day become Janissary colonels, statesmen who might one day return to their home region as governors, or even Grand Viziers or Beylerbeys (governor generals).

Some of the most famous Janissaries include George Kastrioti Skanderbeg, an Albanian who defected and led a 25‑year Albanian revolt against the Ottomans. Another was Sokollu Mehmed Paşa, a Serb who became a grand vizier, served three sultans, and was the de facto ruler of the Ottoman Empire for more than 14 years. |

| |

Deli Sinan fighting against the Hungarian Eugene, 1526.

Topkapi Sarai Museum, Ms Hazine 1517. A detail from folio 212a.

Source: p. 133 from Esin Atıl: Süleymanname. Washington 1986.

Deli Sinan (left) fighting against the Hungarian Eugene, 1526. (L) |

|

|

|

| |

|

Characteristics (W)

The Janissary Aga, Commander-in-Chief of the Janissaries, workshop of Jean Baptiste Vanmour, 1700 -1737. |

|

|

| |

|

The Janissary corps were distinctive in a number of ways. They wore unique uniforms, were paid regular salaries (including bonuses) for their service, marched to music (the mehter), lived in barracks and were the first corps to make extensive use of firearms. A Janissary battalion was a close-knit community, effectively the soldier's family. By tradition, the Sultan himself, after authorizing the payments to the Janissaries, visited the barracks dressed as a janissary trooper, and received his pay alongside the other men of the First Division. They also served as policemen, palace guards, and fire fighters during peacetime. The Janissaries also enjoyed far better support on campaign than other armies of the time. They were part of a well-organized military machine, in which one support corps prepared the roads while others pitched tents and baked the bread. Their weapons and ammunition were transported and re-supplied by the cebeci corps. They campaigned with their own medical teams of Muslim and Jewish surgeons and their sick and wounded were evacuated to dedicated mobile hospitals set up behind the lines. |

| |

Banquet (Safranpilav) for the Janissaries, given by the Sultan. If they refused the meal, they signaled their disapproval of the Sultan. In this case they accept the meal. Ottoman miniature painting, from the Surname-i Vehbi (1720) at the Topkapı Palace Museum in Istanbul. |

|

|

|

|

These differences, along with an impressive war-record, made the janissaries a subject of interest and study by foreigners during their own time. Although eventually the concept of a modern army incorporated and surpassed most of the distinctions of the janissaries and the corps was eventually dissolved, the image of the janissary has remained as one of the symbols of the Ottomans in the western psyche. By the mid-18th century they had taken up many trades and gained the right to marry and enroll their children in the corps and very few continued to live in the barracks. Many of them became administrators and scholars. Retired or discharged janissaries received pensions, and their children were also looked after. |

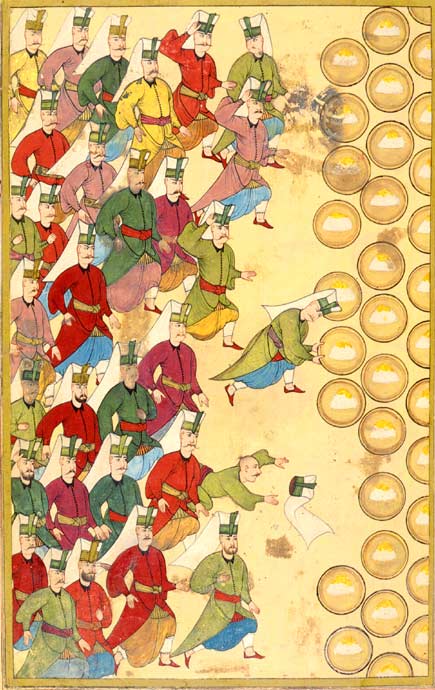

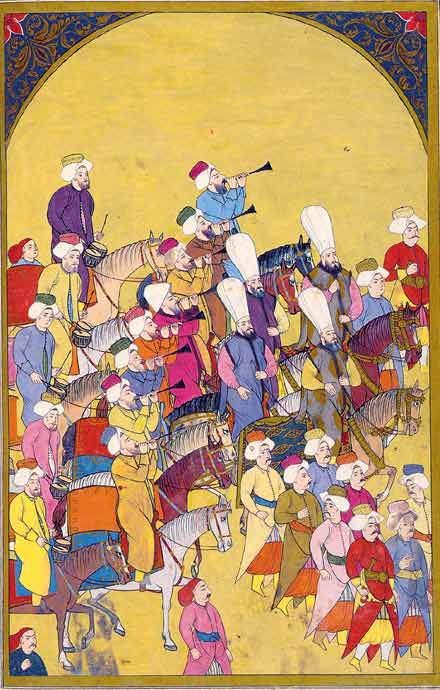

Janissaries marching to Mehter martial tunes played by the Mehterân military band. Ottoman miniature painting, from the Surname-i Vehbi (1720) at the Topkapı Palace Museum in Istanbul. |

|

|

Revolts and disbandment (W)

As Janissaries became aware of their own importance they began to desire a better life. By the early 17th century Janissaries had such prestige and influence that they dominated the government. They could mutiny and dictate policy and hinder efforts to modernize the army structure. They could change Sultans as they wished through palace coups. They made themselves landholders and tradesmen. They would also limit the enlistment to the sons of former Janissaries who did not have to go through the original training period in the acemi oğlan, as well as avoiding the physical selection, thereby reducing their military value. When Janissaries could practically extort money from the Sultan and business and family life replaced martial fervour, their effectiveness as combat troops decreased. The northern borders of the Ottoman Empire slowly began to shrink southwards after the second Battle of Vienna in 1683.

Janissaries, the end of the 17th century. |

|

|

| |

|

In 1449 they revolted for the first time, demanding higher wages, which they obtained. The stage was set for a decadent evolution, like that of the Streltsy of Tsar Peter's Russia or that of the Praetorian Guard which proved the greatest threat to Roman emperors, rather than an effective protection. After 1451, every new Sultan felt obligated to pay each Janissary a reward and raise his pay rank (although since early Ottoman times, every other member of the Topkapi court received a pay raise as well). Sultan Selim II gave Janissaries permission to marry in 1566, undermining the exclusivity of loyalty to the dynasty. By 1622, the Janissaries were a “serious threat” to the stability of the Empire. Through their “greed and indiscipline,” they were now a law unto themselves and, against modern European armies, ineffective on the battlefield as a fighting force. In 1622, the teenage Sultan Osman II, after a defeat during war against Poland, determined to curb Janissary excesses. Outraged at becoming "subject to his own slaves", he tried to disband the Janissary corps, blaming it for the disaster during the Polish war. In the spring, hearing rumours that the Sultan was preparing to move against them, the Janissaries revolted and took the Sultan captive, imprisoning him in the notorious Seven Towers: he was murdered shortly afterwards.

In 1804, the Dahias, the Jannisary junta that ruled Serbia at the time, had taken power in the Sanjak of Smederevo in defiance of the Sultan and they feared that the Sultan would make use of the Serbs to oust them. To forestall this they decided to execute all prominent nobles throughout Central Serbia, a move known as Slaughter of the Knezes. According to historical sources of the city of Valjevo, heads of the murdered men were put on public display in the central square to serve as an example to those who might plot against the rule of the Janissaries. The event triggered the start of the Serbian Revolution with the First Serbian Uprising aimed at putting an end to the 300 years of Ottoman occupation of modern Serbia.

In 1807 a Janissary revolt deposed Sultan Selim III, who had tried to modernize the army along Western European lines. This modern army Selim III created was called Nizam-ı Cedid. His supporters failed to recapture power before Mustafa IV had him killed, but elevated Mahmud II to the throne in 1808. When the Janissaries threatened to oust Mahmud II, he had the captured Mustafa executed and eventually came to a compromise with the Janissaries. Ever mindful of the Janissary threat, the sultan spent the next years discreetly securing his position. The Janissaries' abuse of power, military ineffectiveness, resistance to reform and the cost of salaries to 135,000 men, many of whom were not actually serving soldiers, had all become intolerable.

By 1826, the sultan was ready to move against the Janissary in favour of a more modern military. The sultan informed them, through a fatwa, that he was forming a new army, organised and trained along modern European lines. As predicted, they mutinied, advancing on the sultan's palace. In the ensuing fight, the Janissary barracks were set in flames by artillery fire resulting in 4,000 Janissary fatalities. The survivors were either exiled or executed, and their possessions were confiscated by the Sultan. This event is now called the Auspicious Incident. The last of the Janissaries were then put to death by decapitation in what was later called the Tower of Blood, in Thessaloniki.

After the Janissaries were disbanded by Mahmud II, he then created a new army soon after recruiting 12,000 troops. This new army was formally named the Trained Victorious Soldiers of Muhammad, the Mansure Army for short. By 1830, the army expanded to 27,000 troops and included the Sipahi cavalry. By 1838, all Ottoman fighting corps were included and the army changed its name to the Ordered troops. This military corps lasted until the end of the empire's history. |

|

|

|

Janissary — OTTOMAN MILITARY (B)

Janissary — OTTOMAN MILITARY ( (B)

Janissaries sported snazzy uniforms and kitchen-based titles. |

|

|

| |

|

Janissary, also spelled Janizary, Turkish Yenıçerı (“New Soldier” or “New Troop”), member of an elite corps in the standing army of the Ottoman Empire from the late 14th century to 1826. Highly respected for their military prowess in the 15th and 16th centuries, the Janissaries became a powerful political force within the Ottoman state. During peacetime they were used to garrison frontier towns and police the capital, Istanbul. They constituted the first modern standing army in Europe.

The Janissary corps was originally staffed through devşirme, a system of tribute by which Christian youths were taken from the Balkan provinces, converted to Islam, and drafted into Ottoman service. Subject to strict rules, including celibacy, they were organized into three unequal divisions (cemaat, bölükhalkı, and segban) and commanded by an ağā. In the late 16th century the celibacy rule and other restrictions were relaxed, and by the early 18th century the original method of recruitment had been abandoned, opening the ranks to Muslim Turks. The Janissaries were known particularly for their archery, but by the 16th century they had also become a formidable firepower contingent.

Being an Ottoman Janissary Meant War, Mutiny, and Baklava. |

|

|

| |

|

The supreme prowess and discipline of the Janissaries allowed them to become increasingly powerful in the palace. From the reign of Bayezid II (1481-1512), they regularly required sultans to provide extra pay in exchange for the support of the corps. The maintenance costs of the armed forces proved increasingly unaffordable for the empire, however, and augmented the growing tensions between the Janissaries and the sultan. An attempt by Osman II (1618-22) to discipline them and cut their pay led to his execution at their hands. They frequently engineered palace coups thereafter. In one instance, they conspired with court officials and overthrew İbrahim for his sheer incompetence in governance.

In the early 19th century the Janissaries resisted the adoption of European reforms by the Ottoman army. Their end came in June 1826 in the so-called Auspicious Incident. On learning of the formation of new, Westernized troops, the Janissaries revolted. Sultan Mahmud II declared war on the rebels and, on their refusal to surrender, had cannon fire directed on their barracks. Most of the Janissaries were killed, and those who were taken prisoner were executed. |

|

|

|

|

|

|